So I have an EU passport, now what?

On healing the wounds of naturalization, duty aka wājib, and decolonising therapy.

When I say my entire life has revolved around getting an EU citizenship, I’m not exaggerating. Every decision I took in adulthood—from what to study in college, to what career path to pursue, to which country to build a life in—was a cobblestone on my path to naturalization.

For most people, the world is not an oyster; it’s a tightly shut clam we must force open by obtaining the right documentation.

The calculated decisions I made as an adult were based on simple desires I had as a child, like the desire to travel the world and have access to masterpieces hanging in Western museums. But the strongest desire has always been to live with a sense of perpetual safety. Above all, the 'first world ' meant the absence of threat, of not having to build an entire life while waiting for the other shoe to drop.

But I did lose something in my pursuit of this safety, my sense of self.

You can’t therapize your culture out of you

After Western Europe accepted me as one of its own, and sealed its approval with paper and ink, I now have the mental space to read the fine print, and I don’t like what I’m discovering. I’ve consented to things that fundamentally clash with who I am and what I value.

One of my biggest motivations for pursuing citizenship in the Netherlands, where I’ve lived for the past ten years, is their family reunification program. You can take a girl out of the Middle East, but you can’t take the Middle East out of the girl; my family will forever be an extension of myself. Besides, I’m the eldest daughter, a double whammy of 'co-dependency'.

For a long time, I found comfort in this prospect, no matter how hard things got for me in Western Europe, no matter how lonely or uprooted I felt, I told myself that everything would eventually pay off—soon I’d be able to extend my safety net to my parents and sisters. Decentring myself gave me a sense of peace.

But I was thinking from the perspective of my culture, where 'family' means 'extended family', whereas family in The Netherlands means something else. If you’re above eighteen, the title only applies to your partner and children, i.e. your nuclear family.

My plan was no longer viable; my safety net was mine and mine alone.

I discovered this the day after my naturalization ceremony. With my new papers in hand, I finally felt equipped and brave enough to read through the entire reunification process on the IND website. I felt stupid and silly, I’ve visited that page multiple times but I’ve only skimmed through it. It felt useless to focus on something I could do nothing about. But how could I miss this important detail?

I realized then and there that I don’t know who I am if I can’t share what I have with the people I love, whatever it is, and that makes me fundamentally different from Western Europeans. It’s not accumulating that feeds me, especially when I know someone around me is hungry, what feeds me is my ability to feed others.

I can’t close my eyes and live a life absolved of 'duty'. But duty is a dirty dirty word in Western culture. One that you have to rub off your tongue in therapy sessions

What is duty aka wājib?

As the eldest daughter from a Middle Eastern family, there will always be 'duty' on my table.

In Lebanon, duty is synonymous with honor. You have a duty to your land, a duty to your family (nuclear and extended), and a duty to your community. We call it 'واجب' (Wājib). It is an absolute honor to fulfill your duties—to be of service and help. We get a sense of fulfillment and joy from being dutiful, it feeds us and keeps us going through hardship.

There’s been a lot of talk about Lebanese resilience throughout history, a society that managed and continues to manage to stay connected and efficient in the face of tragedy after tragedy. And I think at the root of it is this inextinguishable desire to be useful and helpful to others; to attach yourself to a higher cause. But we’re not perfect, and can also end up overdoing it, by giving from an empty well for example, or by enmeshing with collective identities like political parties.

In contrast, to be individualistic and to only pursue your desires is considered shameful and antisocial. There is no individual identity without belonging to a community, and there is no community without duty and obligation.

But isn’t that exactly what the West is built on, a lack of duty and obligation towards others, and a constant pursuit of personal desires at the cost of community?

Apathy, I’ve learned, is a popular Western bloodsport, disguised as morality, reason, and even spiritual enlightenment.

So naturally, my sense of duty is unreasonable in the West, pathological even.

I have tried to therapize my way out of it, suppressing fundamental parts to feel assimilated. However, my process of decolonization keeps revealing that my personality was built around an entirely different set of values, and a big chunk of these values will never fit the Eurocentric model of a 'healthy psyche' where caring too much is a problem.

It’s not me who needs to change, it’s the West that refuses to budge and see things from different perspectives, clutching its pearls every time its notion of reality is challenged.

What is healing?

The latest war in Lebanon peaked last October and coincided with my Dutch naturalization ceremony, taking place on October 7th. The irony of that date is not lost on me. The whole thing felt like a cruel joke. I was finally getting what I wanted and worked hard for against the backdrop of shock, fear, and grief while reconciling with this new 'status' that wouldn’t allow me to protect my family from bombs financed by Western governments like mine.

For all of October and most of November, I woke up every morning to footage of familiar places collapsing to dust, and to stories of massacres on one end, and stories of complete dehumanization by the Western media on the other. My people, loving, caring, and multidimensional, were reduced to caricatures and reductive narratives to benefit the West’s agenda.

I felt overwhelmed by emotions that nothing and no one could contain. The only thing that contained me was talking to my family in Beirut, who amidst the crisis were able to access ancestral wisdom that I didn’t have access to.

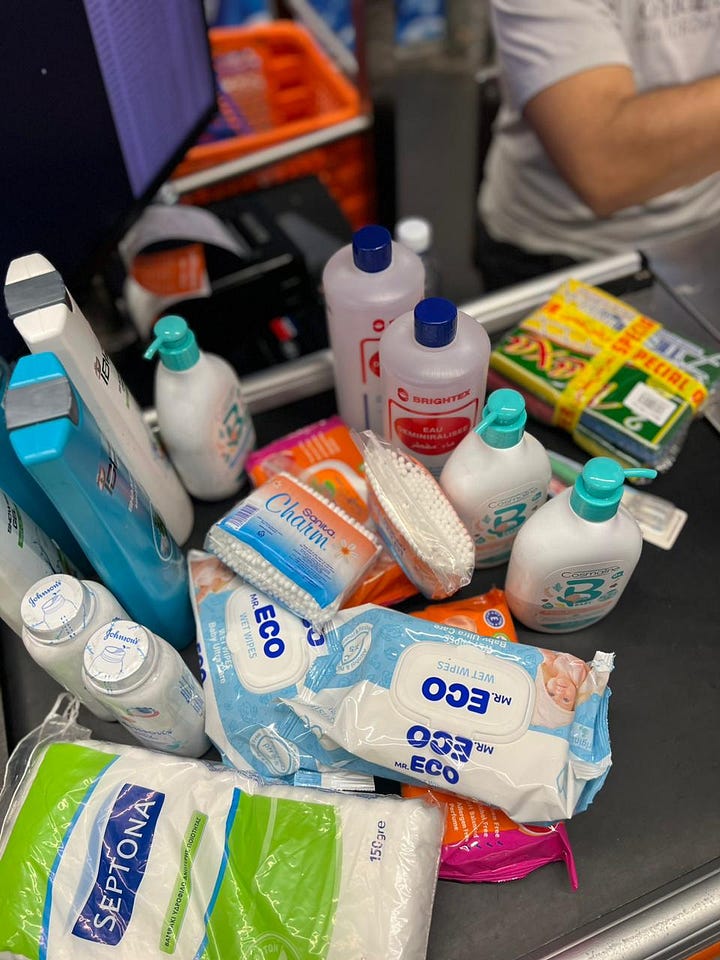

Just a couple of days into the war my sisters pitched an idea to me, they wanted to create donation boxes that met basic and urgent needs so they could distribute them amongst people recently displaced from South Lebanon. We grew up in that part of the country and were also displaced by war back in 2006, we all had a deep sense of duty toward our people, especially now that we were in a more 'privileged' position.

None of us had any experience in mutual aid operations. My sisters were powering through sleeplessness, exhaustion, and terror enforced as collective punishment on the entire country by the IOF, whose relentless bombing campaigns would start daily in the middle of the night. And I was powering through insomnia and night terrors. But somehow we still managed to set up a humble operation.

I focused on raising funds in my immediate network in Europe and they focused on their operations and distribution in Lebanon, together we built a bridge of love and care—a lifeline. Every donation felt like a hug, and every box my sisters delivered felt like a reason to keep going. I don’t know where I would be now if it wasn’t for this mutual aid project that raised 10,000 euros and helped hundreds of people.

I wasn’t doing therapy during all of this, and I didn’t need therapy in the aftermath, this was my therapy. This genuine connection with my community and family, and the transformation of stagnant energy into action, gave me what I needed. I got to see them at their most empowered, letting go of the narrative that they were powerless, while I focused on what I could do and offer instead of what I couldn’t.

I recently discovered that therapy comes from the Greek root 'therapia' and means 'healing'. Before the institutionalizing and industrialization of therapy, we didn’t need degrees and accreditations, there was no centralized authority on healing, knowledge hoarding, or expensive schools and training. Anyone could be a healer if they felt called to it, and anything could be a source of healing, like dance, singing, movement, and community care, to name a few.

But leave it to colonization and capitalism to ruin and commodify things.

Therapy is no longer about fulfilling a calling or a higher collective outcome, it’s about prestige, privilege, and having access to resources. So naturally, it’s also about whiteness and keeping Indigenous and BIPOC people out of the race, devaluing their practices and wisdom that challenge the very existence of oppression and oppressive systems, while simultaneously keeping therapy sessions at an inaccessible price tag.

And if you do have access to therapy, it’s often about keeping you functional and complacent in dysfunction.

I would argue that many of the 'professionals' I’ve encountered on my healing journey in the West shouldn’t be healers, i.e. therapists, and that they do more harm than good to people like me. Like the psychologist who was in charge of my burnout case early last year, and who triggered a dissociative episode. Let’s call her Lotte.

Lotte didn’t want to listen to how the war in Lebanon and genocide in Palestine were affecting my burnout because it triggered her cognitive dissonance. It challenged her view of the natural order of things, and she was trained not to tap into that or to question her training. Whenever I brought up the war she would find a creative way to say: ”But isn’t it always bad there?”. I think my body was eventually flooded with so much anger that I began to dissociate. It would take me days to come back to myself after our sessions. Lotte kept advising me to focus on myself, there’s nothing I could do, after all, so I should accept it, go on little walks, and do a self-care routine to get through the day. Her deepest wisdom was: ”But that is there and you are here”.

Lotte, a white middle-aged Dutch woman, doesn’t understand concepts like 'duty', justice, or the healing properties of service and community care, nor is she interested in understanding them. She was taught to focus on herself, to put her oxygen mask on first, and above all, she was taught that her mental model of the world was superior, one that starts with the individual and not the community.

I don’t have to deal with Lotte anymore, but sometimes I wonder what shitty advice she would’ve given me if I was still under her obligatory care last October. I’m so happy I had the wisdom of my family and people to learn from instead.

What does any of this have to do with having an EU passport?

Since my burnout, I’ve been slowly working on a career in therapy. I’ve seen how broken the system is, how gatekeepy, elitist, racist, ableist, misogynist… you name it. People who haven't decolonized their practices have no business telling non-white, queer, and non-abled-bodied folk what health looks like. But they do, every single day.

For now, I’m in the West, so whatever business I build will be rooted here. But I struggle to dream of a future that doesn’t include the dismantling of this place.

I can’t contribute to this nightmare. I can’t dream of fortune knowing that my taxes will be funneled into proxy wars and genocides in the Middle East and beyond, I can’t dream of a life of leisure and consumption knowing what it costs the planet, and I no longer believe in the myth of Western democracy and morality.

I used to be jealous of privileges like working remotely around the world and traveling without restrictions, but now I see it for what it is: neocolonialism.

I’ve lost respect for the people who built this part of the world because they’ve only ever thought about themselves. They never had a sense of duty towards the planet or its humanity. And now I’m stuck between two chapters, the former full of longing and restriction, and the latter yet to be filled. But with what?

The first time I held my new passport in my hand after it was issued a couple of weeks ago, I barely felt anything. “We’re done,” said the municipality worker, I must’ve been staring at it for a while at the counter. It felt absurd and surreal; so many years of stress, hard work, and insecurity. I said thank you and walked away, it only hit me a couple of days later at Schipol airport.

As I approached my gate I felt strange, holding this thing in my hand, this thick and freshly minted document. My Lebanese passport has always been flimsy, thin, and quick to wear out, with intricate Arabic scripture on its cover and an illustration of a cedar: a native tree and the source of our national pride. I never thought about its deeper meaning, beyond the passport having no real political power or value. It has always been the bane of my existence, making me experience the world as a big fat NO.

But my Dutch one is a deep shiny burgundy, with the Dutch coat of arms in gold: two lions protecting a crowned lion holding a sword and a bundle of arrows—a symbol of monarchy, dominance, and violence. There are no lions in the Netherlands, except for the ones in cages at the zoo. But that is empire for you, and that’s how it works; to rise above nature and people you must first create a hierarchy, to rule over something you must dominate it, and domination requires violence and force

Am I relieved that I have this passport? Of course. Am I grateful? That is questionable. I used to be, but now I’m just angry at all the hoop-jumping we’re required to do for a piece of paper created by the same empire that has its boot on our neck. So no, I won’t kiss, lick, or thank it, for taking what’s mine and then selling it back to me at a higher price.

I don’t know where I’ll end up, but I know that I have a new and reawakened sense of duty. I am not interested in protecting a crowned lion—a monarchy and an empire—my duty or wājib belongs to the ancient trees of this planet and to the people who guard them. I am in the West to dismantle, not to serve.

Hear, hear, sister ❤️

I loved this, this spoke to me so much, thank you for putting this into words