Welcome to my table

On why food is political, friendships that feel like home, and feeding 80+ people.

I can’t think about my culture(s) without thinking about food. I can’t think of myself without thinking about food; my relationship to it throughout the years, and my life rooting and unfolding as a young child in Lebanon, discovering the new place through the lens of its cuisine and all the rituals that surround it. I see food and feeding as the only intimate physical act that is accepted in public and group settings. We bond through eating, it’s there at every social event: birthdays, weddings, funerals, at least where I come from. Which is also why I could never accept the way food is treated in The Netherlands and other neighboring Western European countries, as a mere necessity, a scarce source, and a rare event that you need to be explicitly invited to.

I still remember how shocked I was when I found out that if you find yourself in a Dutch household approaching dinner time, you would either have to leave or you’ll be politely asked to leave instead of being invited to the dinner table. The anecdote alone triggered feelings of shame. In the Global South, there is always enough food, even when there isn’t. Growing up, I was taught that to open a bag of crisps in front of someone and not pass it along is incomprehensible. I have childhood memories of being on the playground while watching my bag of crips travel across the circle of children, and in the corner of my eye I could see another bag appeoaching. No one was worried about their crips being eaten because someone else’s crips would feed them, eventually.

I often find it ironically painful that I ended up in a place with such sharp cultural contrasts surrounding hospitality, generosity, and by extension food. Aside from Qatar, I’ve never lived in a wealthier society. But unlike Qataris, who admittedly tend to be wealthier on average, the general Dutch population is the most frugal I’ve ever experienced, stuck in a mindset of scarcity and complaining when it’s genuinely drowning in more than enough.

In Lebanon, no matter how tight things get, we always say ”الحمد لله” (pronounced: alhamdulillah) which means “praised be God”. There is a general air of thankfulness, of phrases like ”الله بدبر” (pronounced: Allah biddabber) meaning ”God will provide”, and the famous ”إن شاء الله” (pronounced: Inshallah) meaning ”God willing”. When you trust that a higher power will provide and meet your needs you harbor no fear around letting go and giving, and that trust becomes generosity, of which food is but one avenue, although admittedly a fundamental one since its so intrinsic to our survival.

And isn't the fear of not having enough, along with constant dissatisfaction and withholding—and by extension, greed—the root of colonialism and the suffering of the Global South at the hands of the Global North?

Have you eaten yet?

Kinan and I met in Beirut in 2013, back when I was living in Doha and visiting Lebanon on the regular. I wanted to invite my mom to something special, and a friend recommended Kinan’s underground dining concept. I vividly remember the evening we met. The tastefully decorated apartment in the recently trendy Mar Mikhayel, the bubbling noises and appetizing fumes coming from the small kitchen, and Nicolas Jaar playing in the background of the dimly lit dining room. We clicked instantly. I fell in love with his attention to detail, eloquentness, and worldliness. I knew I wanted to get to know him, but I didn’t know we would end up becoming such close friends.

Three years later, we both found ourselves living in Northern Europe, me settling in Amsterdam, and him in Copenhagen. It was one of the toughest years of our lives, and we often found ourselves connecting on Instagram. In November 2016, we finally took the first step in creating what would later become a string of ritualistic visits.

On my first morning in Copenhagen, I was woken up to a table full of scrumptious food; velvety eggs scrambled to perfection, crispy bacon, freshly squeezed orange juice, oatmeal, and danish pastry. It had been a while since someone had cooked for me, and in the harsh reality of Northern winter, that kind of care was the closest I had felt to home since moving to Europe. I returned the favor by making borscht, a dish my Azeri mother often made in winter.

In our cultures, his being Syrian and mine being Lebanese, “have you eaten yet?” "أكلت؟" (pronounced: Akalt?) is an expression of love and care. My friendship with Kinan can be summarized in that one sentence. Not just because we are foodies coming from profound food cultures, or because Kinan is a natural and incredibly talented cook and professional feeder, but because our food has become our stabilizing keel in the sea of migratory uncertainty and shifting identity. It’s the vessel through which we continue to resist Westernization. It’s where and how we process our grief, longing, and love, together.

Sofrat Kinan & Tania at murmur

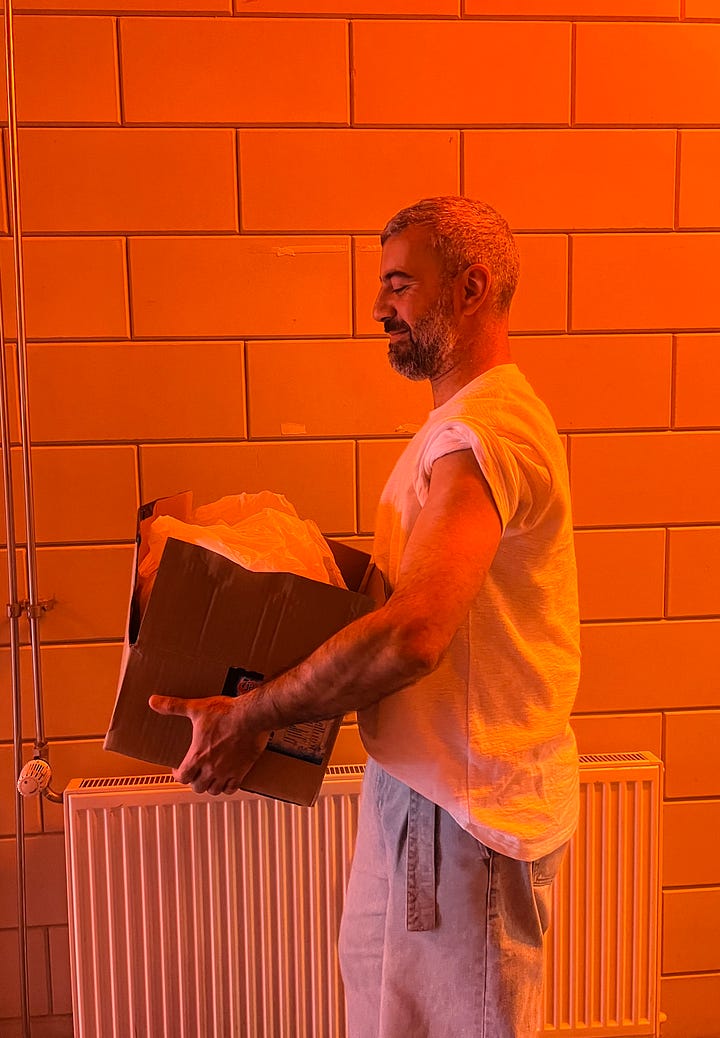

Eight years after that first visit, Kinan and I found ourselves in the tiny kitchen of murmur in Amsterdam, blending tahini, chopping cilantro, and catching up after almost a year of not seeing each other. Kinan now runs a one man catering side hustle in Copenhagen, and I’m still girltossing my way through summer, open to new experiences and forms of labor that don’t include girlbossing. I don’t remember exactly how and why we thought hosting a Lebanese/Syrian food pop-up for eighty plus people is a good idea, having never done it together before, but it just made sense.

Before all the cutting, roasting, and sautéing, we had multiple conversations about the concept. We didn’t just want it to be food without context, we wanted to say something.

When it comes to Syrian cuisine, Kinan is a very conscientious cook, he doesn’t believe in adjusting recipes and flavors to serve the preferences of European tastebuds. You will never find mango in his hummus or labneh with his meat (I’m looking at you The Lebanese Sajeria). He doesn’t believe in pleasing, he believes in historical accuracy and decolonizing our cuisine that is witnessing a wave of appropriation, and in the case of Palestine, complete erasure and theft. And when it comes to storytelling and poetry, I don’t believe in holding back to protect and shelter the Global North from its impact on the Global South. I say things as they are using my own personal lens as a filter. I think too many first generation immigrants died at the altar of assimilation, internalized colonialism, and the loss of identity and sense of self for the illusion of belonging.

The way I see it, belonging is a two way street, it’s not a test of how much of yourself you can relinquish for a seat at a table that is deliberately designed to exclude you. And the new generation of immigrants such as Kinan, me, and many of my Arab friends are much more aware of what we bring to the table. If anything, we know we deserve our own table, and we see our presence in the West as a pragmatic exchange: we give you our magic, youth, and labor, and you give us papers that open doors that you otherwise keep shut. You need us more than we need you, and you’re not doing us a favor, this is just an exchange.

I also believe it’s about time we stop changing ourselves and our ways for acceptance. Why is it our job to shelter our European friends and colleagues from the painful reality of Arab diaspora? Why do we keep our stories to ourselves when they have the power to build bridges, understanding, and connection?

So we served our food as it is supposed to be served: in generous portions, with liberal amounts of garlic and lemon, no unnecessary spices, condiments or garnishes, and doused in extra virgin olive oil from Syria. We refused to welcome people to an empty table, which goes against our tradition of a cheeky little complimentary plate of olives and/or nuts and bread. And of course, everything was served with a side of poetry.

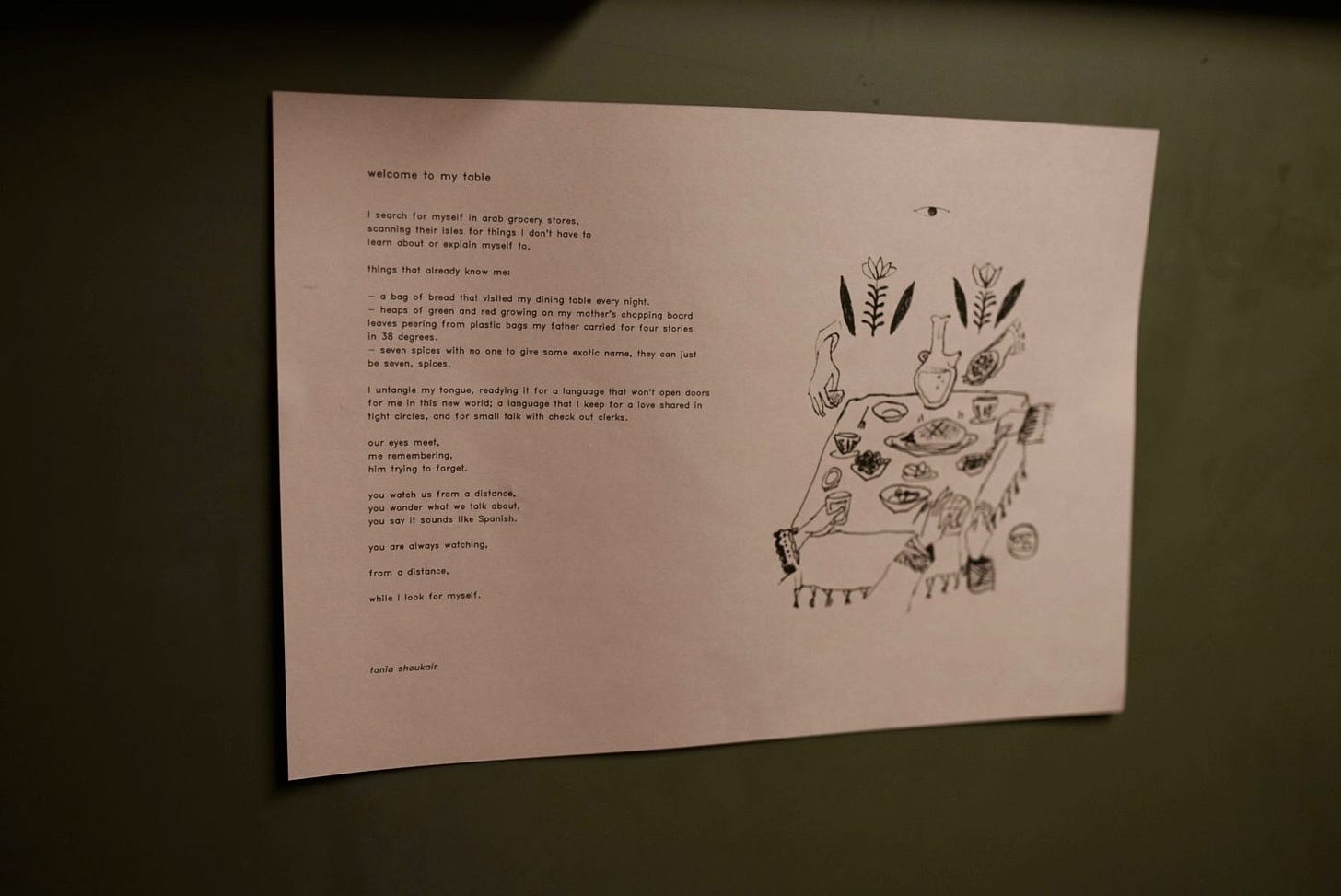

A poem about grocery shopping in diaspora

Our social media post included the following text:

”Sofrat Kinan & Tania is an invitation to mindful appreciation. The word “sofra” in Arabic refers to a table or a spread of food, symbolizing hospitality and the sharing of dishes. Traditionally, it carries the spirit of welcoming travelers and is linked to the word “safar” meaning traveling. You are invited to not only enjoy the delicious flavors of the region but also to consider how they traveled across the world to end up on your table.”

I didn’t know what to write about at first. But as I started going around town doing research about available produce, and exchanging conversations in Arabic with grocery store owners, it all came to me.

I search for myself in Arab grocery stores, scanning their isles for things I don’t have to learn about or explain myself to, things that already know me: - A bag of bread that visited my dining table every night - Heaps of green and red growing on my mother’s chopping board - Leaves peering from plastic bags my father carried for four stories in 38 degrees - Seven spices with no one to give them some exotic name, they can just be seven, spices I untangle my tongue, readying it for a language that won’t open doors for me in this new world; a language that I keep for a love shared in tight circles, and for small talk with cashiers. Our eyes meet, me remembering, him trying to forget. You watch us from a distance, you wonder what we talk about, you say it sounds like Spanish. You are always watching, from a distance, while I look for myself.